Creating the Impossible World: An Introduction

Sasha Saben Callaghan & Harry Josephine Giles

Not Going Back to Normal is a provocation about how things are and an idea for how things could be. This gallery manifesto gathers disabled artists in their diversity, rage, and imagination to call out the institutional ableism in the Scottish arts and picture a future in which disabled artists are central.

The established ways of working in the Scottish cultural scene consistently fail those who are labelled ‘hard to reach’ but who should be more accurately described as ‘easy to ignore’. The representation of disabled people in the creative industries is woefully small, and in some areas the numbers are falling. Targets are set and never reached. Well-meaning policies are written and then quietly shelved when they fail. Report after report claims to identify the problem and yet disabled artists remain underpaid, outside, and stuck at the bottom of the stairs.

We were commissioned by a consortium of visual and gallery arts organisations to make art about the barriers faced by disabled artists in Scotland. We know those barriers by heart, just as every disabled person does. The structures which marginalise us are easy to identify; winning the resources to change them is the challenge. As we considered how to respond to the call, the coronavirus pandemic hit and sharpened all the problems and possibilities of disability arts.

Suddenly, many of the access measures disabled people had been calling for decades – remote working, unconditional income support, online events as standard – were possible, where previously we were told they were just too difficult. But at the same time many of us were experiencing greater isolation, deeper medical discrimination and more extensive social murder. The conditions which oppress disabled people were sharpened even as more of the answers came into view; the threat to disabled futures intensified even as more people than ever came to understand accessibility, isolation, shielding, vulnerability, risk.

But although the times were frightening, we wouldn’t choose to go back to what came before. We were never normal, normal never worked for us anyway, normal was already silencing our voices and killing our friends. So instead of a wish for normality, we asked disabled artists to name the problem and picture the world they wanted to see. We wanted to hear about extravagant desires and wild ambitions. We asked:

What would art be like if it was always centred on disabled people?

How is art in Scotland set up to exclude disabled people and how would you change that?

Can art ever include disabled people in a society which excludes us?

Has the pandemic changed things, and what has it made clearer?

If you could say anything to Creative Scotland and the institutions they support, what would it be?

Our artists have responded to these questions in many ways. Some have written full-blown point-by-point policy manifestos for arts funders. Some have written pleas from the heart to understand disabled conditions. Some have reflected with joy on the creative and access possibilities of lockdown. Some just chose to share art about the richness of their disabled lives. And some called out the terms of our questions in the first place.

As well as the gallery manifesto, we held online discussions to explore the same questions. Alongside projects like the #WeShallNotBeRemoved and a fantastic essay series at Disability Arts Online, we were part of a months-long, wide-ranging conversation about what excludes disabled people and how we are building a future.

The problems our participants identified were deep and systemic, extending beyond individual galleries to the whole structure of society. Except for a privileged few, a paid full-time career as an artist is a distant dream. Insecurity is widespread in the Scottish Arts scene, but the impact is felt disproportionately by disabled artists. The further an artist is from the mainstream, the worse they will be hit by any crisis. Lack of financial stability, for example being forced to subsist on Universal Credit and sporadic micro-commissions, is a desperate way for anyone to live. The stress this uncertainty causes is a significant factor in deterring disabled people from participating in the arts.

Discrimination and exclusion from the arts begins early. If your school art room isn’t accessible, or you’re in segregated classrooms with poorer supplies, you might never be supported to make art in the first place. If your local creative workshops don't have ramps, you'll never get in. If studios don’t have induction loops and tactile signs, you’re excluded. If the art you make is too weird for art school, you’re shut out from professional development. The artists who do make it through to the point of being commissioned by galleries are fewer, less well-supported and have had fewer chances for professional development.

The tyranny of networking is a major obstacle to D/deaf, disabled and neurodivergent artists. Social events like salons and launches extremely difficult to deal with and the ableist concept of ‘working the room’ causes anxiety. This feeds into a vicious circle as the creative sector in Scotland (and pretty much everywhere) is constructed around the notion of making contacts and knowing ‘the right people’. Without these interpersonal relationships and shared sense of identity, it is hard to build the social capital needed to establish even low-paid careers in the arts.

For a sector which is supposed to encourage originality, there is a depressingly entrenched expectation within the arts that everyone will think and behave in a broadly similar way. ‘Normal’ is the default setting. Whenever someone deviates from the imposed norm, when they say or do something which is seen as ‘challenging’, ‘eccentric’ or ‘off message’, there is an embarrassed silence and a rapid move to the next subject. The result is that a person who is perceived as ‘awkward’ and ‘difficult to relate to’ is left on the margins, undermined, isolated and invalidated. Add to that the problem of ‘becoming the problem' when asking for an access measure or calling out discrimination, and many of us just give up.

And finally, even if you do get past all these barriers, most of the time the only art we’re asked to make is art about being disabled, and we’re more likely to be commissioned to do outreach and consultation projects than just to make art. We’re stuck in the double-bind of otherness, either excluded or tokenised, refusing to be restricted to our oppressions but not wanting to be silent about them either.

Faced with all this, we think that we have been too nice and too patient when we ought to have been feral in fighting for the recognition we are due. This is not a polite report. It is a manifesto of demands.

There is no one answer, and the artists in our gallery offer many options and many questions. As curators of this manifesto, we’d like to highlight just a few beginnings.

First, institutions must recognise that the arts sector is a mirror, reflecting the biases and attitudes of wider Scottish society. It is just too easy to talk about the need for more diversity training and equality action plans – we have been here so many times before and it has achieved little. An accessible arts sector is impossible in an inaccessible society: deep, long-lasting change requires a tremendous social shift. The arts should be part of demanding and making that change, not lagging behind it.

Second, we need to stop pretending to ourselves that a few token appointments or commissions can change the dominant ableist, neurotypical culture within arts institutions and organisations. Individuals shouldn’t be expected to take up this heroic mantle and it is unfair to place such a massive level of responsibility on them. Institutions must demand better of themselves, and artists must resist taking the tick box role of covering up the structural problem.

Third, as the lead funding body, Creative Scotland needs to put its own house in order by proactively seeking out disabled/D/deaf and neurodiverse artists to invest in, work with, and lead in its management and Board. This will take time, but an immediate step would be to pay a diverse range of disabled people to lead the change, the less accommodating and the less normal the better. This change should be uncomfortable, and it should be led by resources, not reports. Art ought to be about risk and daring, not always playing it safe.

Fourth, in order to promote safety and security for all artists, Creative Scotland should make the case for unconditional income support for all. During the pandemic, although under intolerable conditions, many people in the UK had their first taste ever of being given resources to live without having to work under threat of starvation, and many had their first experience of support without means testing. The creative possibilities of this are immense. Whether we call it Universal Basic Income or otherwise, arts institutions should highlight how this kind of support will enable disabled and other marginalised people to participate in the cultural life of Scotland.

And finally, we would say to the organisations and institutions receiving support from Creative Scotland that, unless they can demonstrate clearly how they will work accessibly from now on, and unless their workforce, commissioned artists, community participants and audiences are at least 20% disabled, as is the working age population, their funding will cease within six months. This approach ought to concentrate their collective minds.

Experience has taught us to be pessimistic about the potential of any report, or indeed manifesto, to make the institutional change we need. We’ve been here before and we’ll be here again. But our lives have taught us to be always optimistic about the radical joy of disabled artists, and the huge strength disabled people have in forcing change. Whether or not you change, we’ll still be wheeling into the future, building new institutions with our collective hands, feet and teeth, socialising with each other in mad and strange ways, and creating the impossible world.

* * *

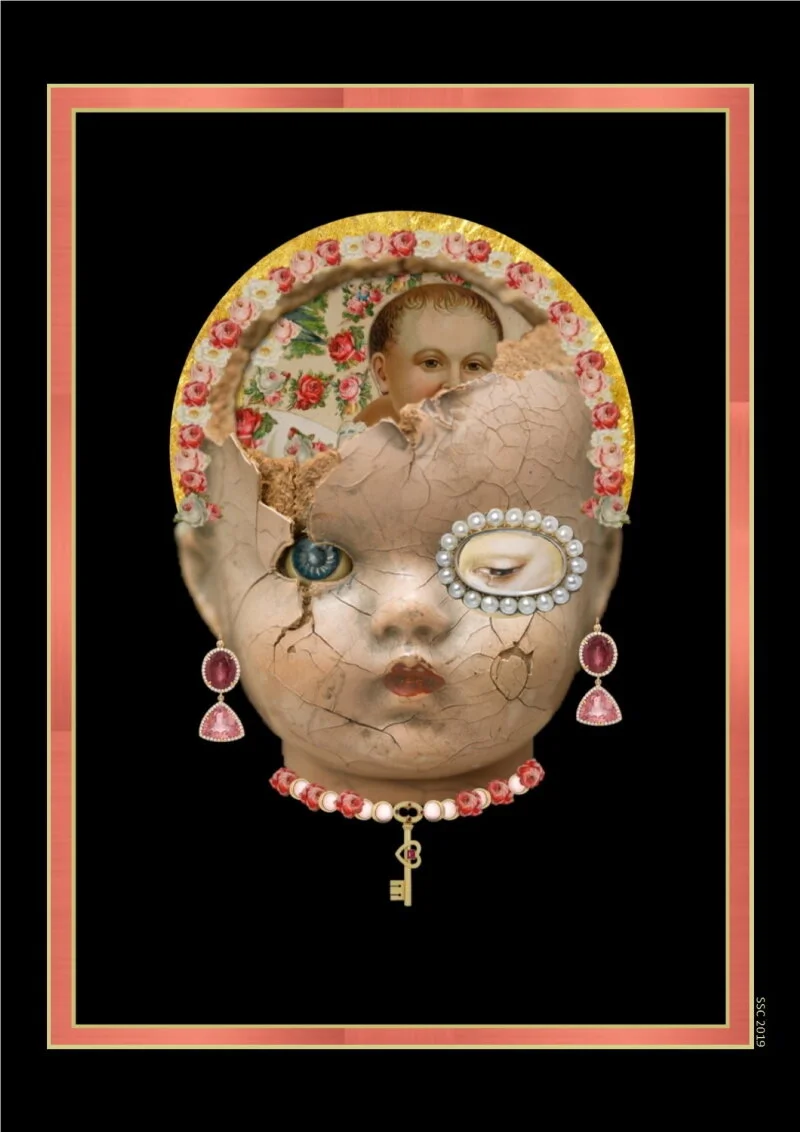

Sasha Saben Callaghan is a writer and digital artist, living on the east coast of Scotland. She was a winner of the 2016 ‘A Public Space’ Emerging Writer Fellowship and the 2019 Pen to Paper Awards. Her illustrations have featured in a wide range of journals and magazines. Sasha’s lived experience of disability and impairment is a major influence on her work. instagram.com/sashasaben

Harry Josephine Giles is a writer and performer from Orkney who lives in Leith. Their latest book is The Games from Out-Spoken Press, shortlisted for the 2019 Saltire Prize for Best Collection. They are studying for a PhD at Stirling, co-direct the performance platform Anatomy, are now touring the poetry-music-video show Drone. Harry Josephine is trans and autistic. harryjosephine.com